At 14, Joseph Shrock went to work for his father’s construction business.

He had completed his formal education after finishing eighth grade in his Amish community in rural Ohio.

His father usually had a crew of two or three workers, repairing old barns, framing, laying block, whatever customers needed.

“He had an engineer-type mind,” recalls Joseph. “He could fix anything.”

But his father didn’t enjoy reading plans and the business side of construction.

“He was kind of the type that would barely have a business card,” Joseph says. “He didn’t have a tax ID number.”

So Joseph began reading blueprints and organizing the projects.

“I would handle that stuff at a really young age,” he said. “As I got to 17, 18, 19 years old, I was talking my dad into taking bigger projects.”

“My dad was just really good at letting me run the stuff,” Joseph adds. “It was a God-given talent that I had.”

He recalls talking with a college student who would work with his father’s business during the summers about taking some courses at a technical college on how to read blueprints. By then, the business was doing larger projects, such as apartment buildings and motels.

The college student chuckled. “You’ll know more about the plans by now than the guy teaching the course,” he told Joseph.

“I’m not saying it to brag,” Joseph says decades later. “It’s just that I loved it.”

Ten years after starting with his father, Joseph filed to establish a construction firm.

Today, he owns and runs Shrock Premier Custom Construction, which employs 35 people and has annual revenues of $14 million.

Doing business from a phone booth

Ruthie Deal went to work for Joseph about 15 years ago as his assistant. She soon learned he wasn’t the typical boss.

For starters, Joseph was a member of a strict Amish church district that prohibited phones in the home. And Joseph’s office was in his home.

“So he would go down to the end of the road,” Ruthie recalls, “and do all of his calls from the little phone booth. Twenty degrees below zero, and he’s in his phone booth making phone calls.

“He didn’t have a fax; he didn’t have any electronic stuff. All of his checks for a long time were handwritten, and his proposals were all handwritten.”

Working from her home, Ruthie quickly made a change.

“We got a fax machine as soon as I started,” she says.

When asked about working from a phone booth, Joseph laughs.

“It got cold,” he said. “You would learn to get ‘er done,” he says.

But those 20 years of working from a phone booth didn’t hinder him, he says.

“That didn’t keep me from being successful,” he says. “It took more effort was all. I might have to work more hours. But I made sure that every move counted.”

“People have it too easy now,” he adds. “I am convinced that it’s not the difficulties that keep people from being successful.”

Focus on quality

As Joseph led the company to take on bigger projects as a subcontractor, contractors began to take notice of Joseph’s talents.

Soon, the jobs began rolling in – commercial work and then homebuilding.

“We were traveling quite a bit in those early years,” he recalls. He realized, though, that the travel and pace were burning out his crew.

“If I want to keep these employees, I’m going to have to create an environment where they’re going to stay, where they can take care of their families,” he recalls.

So he turned the company’s focus to custom houses and other custom work, projects that took more talent, more foresight and kept them closer to home. He would preach to his crews to focus on quality.

“Next thing we knew,” he says, “we’d have people trust us with their high-end projects.”

And that trust continues to build, as the company strengthens its relationships with its customers.

One such relationship has led to a $20 million, 2,200-seat sanctuary the company will soon embark on for Faith Life Church. Shrock built the pastors’ home, and 10 years ago, they called on the company to complete an addition to their church. The church had trouble with previous contractors and had become frustrated.

Shrock redesigned the addition, saving them money while still giving them the look they wanted. “Now they’re trusting us with this $20 million addition,” Joseph says. “And we’ve never done a $20 million church sanctuary before.”

Gary Keesee, senior pastor of Faith Life Church, says the Shrock company took on the church’s first addition project during the Great Recession even after the bank had warned the church that it may not be able to provide the promised line of credit.

“Amazingly, Joseph said, ‘We’re going to finish the building,’” recalls Keesee. “He finished the building without assurances that the funding was there.”

“He exceeded all our expectations in not only rescuing what was already a difficult project,” says Pastor Drenda Keesee, “but taking it to our expectations, our desire and our dream.”

Moving out of the phone booth

About 10 years ago, Joseph decided it was time to make a change. He was now part of a New Amish Order church district, which didn’t prohibit phones in the home.

Along with himself, all of his employees were working out of their homes.

“We just got to the point where we really needed an office,” he says.

A building came available for sale in the historic Main Street section of Loudonville, which the company bought. It later bought the adjoining building.

“Every office we did in a different type of wood,” Joseph says.

With the adjoining building, the company developed a showroom to display photos of their projects, as well as eight different styles of cabinets the company crafted. Employees also made the furniture.

Two years ago, the company bought another nearby building – a 380,000-square-foot former Flxible bus manufacturing plant.

The company was able to consolidate all of its maintenance shops and storage areas that were scattered around the area. Joseph also brought in two other companies he had started, a prefab wall manufacturing business and fire-, water-, smoke- and mold-restoration business, under the old factory’s roof.

Not only did the factory provide a place for much-needed consolidation, it also helped restore some community pride that had been lost after the factory closed in 1996. It had been a fixture in the small town since 1913, when it first began building motorcycle sidecars. In its heyday in the ’80s, it employed over 1,000 workers manufacturing motor coaches.

“It is a historic building; every family was related to it because their parents and grandparents worked there,” says Lisa Christine, who handles HR and safety for Shrock and who also worked at the factory.

Shrock has invested more than $1 million into refurbishing the old plant, with more investment planned.

Excavation takes off

The consolidations have been a natural result of continued growth over the years. In 2018, the company saw an 80 percent increase in revenue, with its excavation division posting the fastest growth.

The growth has been the result of the company’s ability to adapt to new opportunities.

“We had to be adaptive, because in the beginning, we weren’t professionals at anything,” says Cliff Conner, who helps manage excavation work.

He explains that the company would try new ventures and then the market would turn, and it would have to look for other opportunities.

“Everybody’s experience levels went way up by being so versatile,” Conner says. Now, the company can handle just about any job that comes along.

That has led to some multi-million-dollar campground projects for the Muskingum Watershed Conservancy District and a $5 million gas station project, in which the company handled the entire job – land clearing, water and sewer, plumbing, building the store and other structures.

“All of a sudden, we find ourselves the perfect match,” says Joseph.

He explains that many of the excavation contractors in the area focus on a specialty such as land development, storm water or sewer. So when a project like the campground comes up, it’s hard to compete with Shrock, which can do the total package.

“It seems like we work best at full speed; everything seems to flow better,” Conner says.

The company’s reputation for quality and integrity also tips the scales in its favor.

Dwight Hackworth of Michael Baker International oversaw Shrock’s campground projects for the Muskingum district and appreciated being able to trust the company’s workers.

“I didn’t have to worry about the guys on one job doing something wrong, while I was dealing with another job,” Hackworth says. “Our customer realizes that due to the integrity of Shrock, it saved them money in the long run.”

Employees as fans

Shrock has also made fans of its employees.

“I’ve never seen anything like this,” says company controller Shayne Glass.

He had been wanting to transition from corporate accounting, and he met Joseph about four years ago over lunch one day.

“The more I met with him, the more unique I realized he was, as far as integrity and the values here,” Glass says.

“It’s like family,” adds Teri Derr, the company’s paralegal and contract manager. “Everybody that works here that you meet, they have a personal investment. It’s almost like each one of us owns the company.”

Joseph also believes in helping employees improve their lives, not just at work. Last year, he decided to create a new part-time position for business development. He hired Ross Yoder, an assistant baseball coach at nearby Mount Vernon Nazarene University, to run it.

“We do a lot of leadership training where the idea is to help people with understanding themselves, understanding how they can best connect with the people in their lives,” Yoder says. “Ultimately, it’s not just for the workplace.”

Word of Joseph’s good treatment of employees has spread, to the point where he doesn’t face the challenges many contractors do in finding qualified workers. They come to him.

“Now that things are booming, where people can get a topnotch job wherever they want, I’m getting more calls (from job seekers) than I did during the recession,” he says.

Keeping the faith

Joseph was born and raised Amish, and he and his wife raised their children in the faith. Their first language is Pennsylvania Dutch, but they grew up in communities near non-Amish, learned English and get along well with those inside and outside of the Amish world.

Though part of a New Amish Order church district, the family still adheres to many traditional Amish practices. On their farm where they raise longhorn cattle, they use only solar energy or a gas well dug on their property for power. They also don’t drive cars or trucks, instead driving horse and buggy. To get to work and jobsites, they rely on non-Amish friends and employees for transportation.

Joseph’s son and three daughters all attended Amish school through the eighth grade and then went to work for the family businesses. The family opened a deli and bulk food store, which the daughters run.

Samuel, Joseph’s 26-year-old son, has been through all aspects of the family businesses, including leading construction crews. He began operating a backhoe on the family farm in his early teens – operating such machinery does not violate Amish beliefs – and later performed excavation work on construction sites.

“The goal was to shift him to a little bit of everywhere, and he has been,” Joseph says.

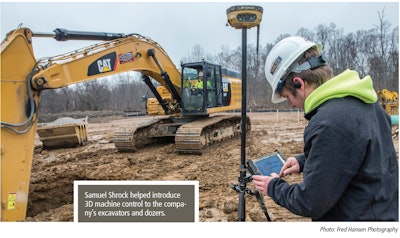

Despite being raised in traditional Amish ways, Samuel loves technology. He uses a drone to make company videos of jobsites. He also helped introduce GPS machine control for company dozers and excavators and then trained workers on it in the field.

“I’m always trying to watch for new opportunities of systems or software that can help us,” Samuel says.

For business, there are no major issues with being Amish, Samuel says.

“I don’t feel like it limits much the way that we do things,” he says.

Joseph believes his faith has helped him become a better leader. He is passionate about leadership and has attended several seminars over the years.

“A lot of the principles that work are biblical principles,” he says of the leadership seminars. “Proverbs 16 has a lot of good principles that you can use in the business world.”

Looking to the future

Being a business leader is always a challenge but being Amish has presented some unique circumstances for Joseph.

“In the conservative Amish world, big business is not looked on as a real honorable thing,” he says. “I spent probably more time and effort trying to keep things smaller than I did trying to grow it.”

But that’s beginning to change.

“I’m convinced if you put the right people in the right place and the right motives and the right energy, you can’t hold it back,” he says.

So he has been developing a long-term succession plan that will allow the company to keep growing and protect the employees, which are about 50-50 Amish and non-Amish.

He and Samuel have been meeting with a non-Amish businessman about eventually owning the company.

“When we made the determination a few years ago to bring another person on board that’s not Amish, that’s when we focused a little more on, OK, let’s go ahead and grow it,” Joseph says. “Samuel and I spent about four years meeting with this person on a monthly basis behind closed doors until we felt comfortable bringing somebody in that had our values, that would take care of the employees, where we could still be involved and be in the leadership positions.”

While Samuel is interested in being involved in the family business, he wants to explore his passion, which is real estate development. He recently began development of a 14-lot high-end gated community near Columbus. Shrock is handling the site development, lot sales and custom home construction – the company’s first such venture. It has already made plans for another 70- to 80-lot development.

“If that’s profitable and it works, that’s going to be another good fit to our company,” Joseph says.

And just as Joseph’s father allowed him to follow his passion, Joseph is doing the same for Samuel.

“Taking over the whole operation would really tie him down,” Joseph says. “So we’re trying to come up with a way he can have his own thing and still be involved in the business.”

As for Joseph, he plans to continue following his passion of helping his employees and community.

“There’s got to be more of a purpose than just generating income,” he says. “There’s a bigger mission. And I think God gave me certain talents for a reason, and I feel good about exercising them.

“Everybody feels best when they’re making a difference, and if you can create that environment and these people can feel like they’re making a difference and they’re helping. …

“I just love it.”